We need Better Hedges (in Public-Interest Technology)

05 Sep 2021

It might seem an improbable choice for someone aspiring to help people. But it was not at all an unusual one in her circles. Cohen was hardly the first person to be impressed by an oft-heard view, espoused by firms like Goldman, that the skills they teach are vital preparation for change-making of any sort. Management consulting firms and Wall Street financial houses have persuaded many young people in recent years that they provide a superior version of what the liberal arts are said to offer: highly portable training for doing whatever you wish down the road. They also say, according to Cohen, “To be a leader in the world, you need this skill set.”

She didn’t capitulate to these notions all at once. She considered jobs in the nonprofit sector that had been advertised on campus or online. Somehow, though, they felt risky to her. Sure she would be cutting to the chase of making a difference, but wouldn’t she be forgoing the skill-building and self-cultivation offered by the private-sector firms? Some of the NGOs she looked at seemed to have no career plan for a young person, no promise of a trajectory of growing responsibility and impact. A lot of these places hired only one or two graduates per year and expected them to find their way with little structure, whereas big firms recruited entire cohorts of them for entry-level analyst positions, referring to them as ‘classes’, subtly playing into their nostalgia for dorm-room days.

– Winner’s Take All - Anand Giridharadas.

What’s the problem?

There often isn’t a good way that someone interested in the public-interest can ‘hedge’. People leaving universities often feel like they aren’t sure how to have a positive impact, and so they hedge their bets to go work at a place like Mckinsey or Google where you know they will get generally good operational skills. Even from the perspective of someone trying to maximize good in the world (like an effective altruist), going to one of the organizations is often genuinely the most logical place for you to work - a key part of being an effective altruist is being effective.

I think that one of the biggest meta-issues in society right now is figuring out how we can send people who are deciding their careers to work on (relatively) important societal causes, while also developing generally useful career capital. This issue underlies nearly any other issue - if we do not incentivize people to work in places with lots of big Problems (with a capital P), the solutions we get will address only the problems that people see; in this case, from the vantage point of Mckinsey consultants and Google engineers.

It’s hard to develop good thoughts about how to align social interest with career development interests; and it makes sense that it should be hard - at its core, nearly any entrepreneur is thinking about this exact issue: how to align the mechanisms that capitalism empowers to your individual goals. The difficulty of this challenge is self-assembling; if it was easy, everyone would do it, and then it would be hard again. Luckily, it is clearly not impossible; as a first-order existence proof: if you think that electric vehicles or space travel are important social issues, Elon Musk has certainly been able to leverage the market to make rapid changes on these social issues.

I am particularly interested in public-interest technology, and while many of the arguments I make are general statements, this post is centered around developing the talent and resource pipelines for public-interest tech. I seek to (begin to) address: Do we need to, and if so, how do we, develop better hedges in public-interest technology. This is my first public post on this issue - while I’m confident I may write naive things, I don’t want to be so afraid of saying something that I miss this opportunity to hone my thoughts on what I consider one of the world’s biggest issues.

Note 1: “As a first-order approximation, I consider something public-interest if it helps a group of people and is likely not to be addressed by the for-profit market (without government or NGO funding). Ads might help the internet be free, but if you don’t go work on them, someone else will — the same is not true for building a homeless shelter.” - Resources for Working in Public-Interest Technology | by Roy Rinberg.

Theory of Change - as an individual and a community member

As individuals and community members, we do not have access to strong economic levers - (except in rare cases) we can’t just throw money at a social cause we care about. However, as individuals, we have some access to social power and an ability to influence what people consider prestigious. This doesn’t feel like that much power, this is difficult to quantify, and predicting the effect of social influence is very difficult; however it shouldn’t be ignored. Even though the percentage of vegetarians and vegans has not gone up in 30 years (animal charity evaluators), vegan food consumption is soaring (plant proteins), in particular alternative meats (the rise of meatless meat, explained). While finding a study documenting the effect has been challenging, I feel confident linking the social pressure from vegans and vegetarians in the 2000s to the eventual economic demand for the alternative meat revolution we are now beginning to see. (Though, as always, perhaps my confidence is misplaced, and I’d be curious what studies exist about the measured efficacy of vegetarian/vegan movements).

In developing models for promoting public-interest, it seems to me that Teach for America (TFA) is a good model to strive for (in spite of criticisms). TFA is a generally prestigious organization that takes young college-grads and directs them to underprivileged schools in places like Central Florida, Buffalo, and St. Louis. Their mission statement is “enlist, develop, and mobilize as many as possible of our nation’s most promising future leaders to grow and strengthen the movement for educational equity and excellence.” For graduates who want to become teachers, TFA provides obvious advantages (name-brand, grad-school benefits, and a strong network in education). However, TFA also creates an ostensibly fantastic way for top college grads who don’t intend to become teachers to hedge - college-grads can go take 2 years to work in a public school that genuinely needs more academic attention, and then because of the brand that TFA has developed, those grads are often connected with what many would consider elite institutions. Alumni from the program frequent institutions like Harvard Business School, Northwestern Law School, McKinsey, and Google.

A suggestion for a call to action

To make my thesis concise (though, not yet precise): we need to make our “hedges” better for society; particularly with regards to tech and its influence on society. And to do this, I advocate for an emphasis in organizations and programs similar to TFA or post-graduation fellowships.

Through most of the rest of this post, I will dig into the TFA model, and look at its strengths and weaknesses.

What is TFA, and what are its stated goals?

“For the uninitiated, Teach for America is an alternative certification program that recruits people to become teachers in high needs schools for a commitment of two years. TFA is a fairly prestigious and selective program (for the past several years, fewer than 15% of applicants were admitted, a lower acceptance rate than that of Harvard Law School). It can be an incredible way to start teaching in a high needs school, but it’s also really hard, and not the right fit for everyone.“ - Should I Consider Teach for America?

The Original idea:

“….Whereas private-school teachers work in comfortable environments, TFA corps members would be asked to work in the most troubled schools. Consequently, in order to get the “best and brightest” into low-income urban public schools, the organization made a key tradeoff: time. As Kopp put it in her thesis, “rather than fighting a losing battle” against higher paying and higher-status opportunities, TFA would opt “not to compete.” Instead, it would request “that individuals take a break from their fast-paced lives to serve the nation.” …. TFA, according to its leadership, has seen it infeasible to ask for more than a two-year commitment to placement sites. “People were opting not to go to law school or medical school . . . and instead pursue teaching,” a former site director noted”

– How Teach For America became powerful

It is not unique:

Teach For America was neither alone nor even first… but would become the most visible, as well as the only truly national response.

– How Teach For America became powerful

It leveraged libertarian/pro-market ideals in a world not unlike 2021:

Kopp noted in her original plan for TFA that the concerns of business leaders about the decline of the American workforce presented an opportunity to secure corporate financial backing, and grants from companies like Union Carbide and Morgan Stanley bore out her claim. She was also well aware of philanthropic support for projects focused on the promotion of equity, and by emphasizing that aspect of TFA’s mission she found a number of friends with deep pockets.

…. TFA’s antibureaucratic, promarket approach was attractive to a new generation of entrepreneurially oriented funders.

– How Teach For America became powerful

It emphasized prestige:

….Kopp sought from the organization’s inception to make TFA exclusive, even if it meant limiting its scale. “I’d like people to someday talk about TFA,” she commented in 1996, “the way they talk about the Rhodes scholarship.” Advancing this aim, the organization, from its origins, has promoted its corps members’ prestigious alma maters, their high grade-point averages, and their SAT scores.…

– How Teach For America became powerful

It has updated its stated goals, and here is an opinion on what TFA’s goals are, in response to criticisms:

…The program was never intended to solve the teacher shortage problem or even to fix public education simply by preparing bright college students to teach for two years,” argued TFA advocate Julie Mikuta in 2008. “Instead,” she contended, “TFA intends to transform public education by exposing these talented people to the challenges of public education and engaging them in figuring out solutions.” Thus, she concluded, TFA’s impact will only be seen in the future, once “alumni take on more visible and influential roles.

– How Teach For America became powerful

Pulling this all in together, TFA’s special sauce appears to have been in focussing its resources on tying prestige to social good, and that’s what our better hedges need to focus on as well.

TFA-like Alternative Models: Fellowships

TFA is not unique, it’s just (one of) the biggest. But nothing in what I’ve been describing so far relies on network effects, and “better hedges” can happen on very small scales. Any single person who is working on something in the public-interest is another person working on something in the public-interest. Individuals, grant-givers, and foundations only need to consider the incentive structures for their specific case.

Prestigious fellowships are an appealing implementation of the TFA model. For example, Princeton’s High Meadows Fellowship funds Princeton graduates to go work in organizations like The Wilderness Society, Climate Central, Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), and the Food Project (TFP). By funding its fellows to directly go work in an organization, those students get:

- Prestige

- The job-security of a 2 year contract

- A soft expectation that they can leave after 2 years.

- And because the position is funded by a fellowship, as opposed to the organization itself, the graduates get to work on more interesting projects, because there is less pressure on the organization to immediately recoup the cost of salaries.

So, while I will continue to advocate for TFA, other instantiations like public-interest fellowships seem like an equally great stand-in.

What does the current job market incentivize?

I would describe a job’s potential positive impact to society and to an individual’s career as:

Societal benefits:

- Direct positive change in a community

- Giving people who later end up being successful/important, experiences that give them a social-justice-based perspective.

Individual benefits:

- Learning useful skills

- Gaining useful/interesting experiences (which enables better decision making)

- Career capital/prestige/improving your resume

- Making money

- Happiness and feeling like you’re making a positive change

It seems like current job-markets advocate for emphasis on individual-benefits 3 and 4, with little external incentives for anything else. And organizations like TFA will never be able to achieve 4, they focus on carefully deploying prestige, in order to tie prestige to societal benefits.

And if Quora is to be trusted, it does in fact do this, through: the brand, the network, short term commitment, and attractiveness relative to other nonprofit options (What’s the appeal of Teach for America to students from top-tier universities?).

When asking what parts of TFA should be emulated ? Specifically, we want to create unique opportunities for individuals to explore working at socially-important places, while also feeling like they are improving their resume (specifically, 1, 3, and 4).

Digging into TFA

We are lucky, we have a fantastic case-study of what something like TFA would look like… TFA. Given all the praise and criticisms that TFA has accumulated over the years, let’s do a deeper dive into what we can and should seek to emulate in our future investigations.

Potential Harms of TFA:

- A common criticism I’ve heard of TFA is that you pay for young (white) people to try something out, experiment, and then leave after 2 years; and the problem is that teaching is something that benefits a lot from individuals remaining in a community, and leaving means that the students themselves are not being benefitted.

-

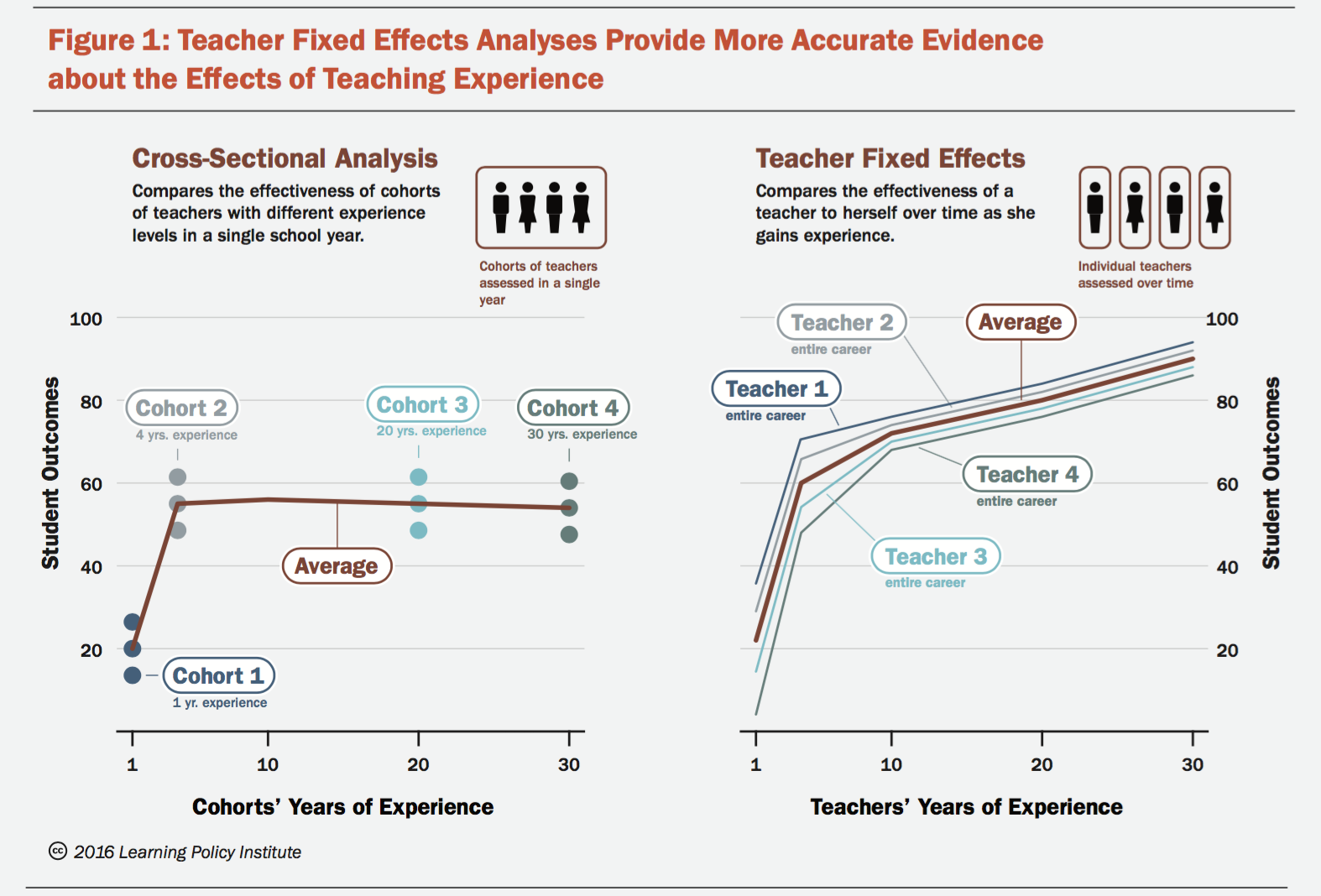

See this chart - the first few years of teaching are dramatically worse for the students than later years. Without encouraging individuals to stay long enough to amortize out the negative effects they have in the first years, we may be doing net harms to communities, for the benefit of young elites. And we should seek to avoid a TFA-like model in situations where leaving the community does not have a strong negative impact (like it does in teaching)

- Negative impressions from ex-TFA-ers (How Teach For America became powerful):

-

Another corps member recalled her experience teaching in Los Angeles: “Sometimes my inexperience was relatively harmless, resulting in botched lessons or an inability to get everything done that I needed to do. Other times my newness had more dangerous consequences–I bungled home visits, didn’t contact Child Protective Services when I should have, and sometimes even failed to keep my students safe….

-

This disappointment caused the principal to lament: “you invest in them, get them to a level of skill, and then they leave. I have to look for stability at school. Last year I hired all TFAers for my vacancies. This year, I’m going to be looking for a significant number of non-TFA teachers.”

-

- A final point: a major critique of TFA that actually echoes one that I hear often of the effective altruism movement is: “institutions working on ‘good’ [within EA, or TFA itself] have no intention of trying to completely uproot our framework, they are just try to make it a little bit better while maintaining their power.” In other words, TFA (like many EA orgs) are not addressing systemic issues (or atleast, enough).

Let’s evaluate “better early-career hedges”

Let’s look even closer at the idea of promoting public-interest (technology) through better hedges, particularly through the development of organizations like TFA or fellowships.

I strongly appreciate the effective altruism framework for evaluating problems (as originally outlines in Doing Good Better):

- Is this area neglected?

- Yes. Though this is only a proxy for neglectedness, I think that people wouldn’t talk about bridging the gap between technologists and policy-makers as much as they do, if these kinds of programs and fellowships existed enough.

- Is this the most effective thing you can do

- I think this is usually a bad question.

- How many people benefit and by how much?

- I suspect a lot; but it’s hard to measure! And there’s always room for harm. The whole point of this post is to make a non-quantitative argument that this is likely a good idea.

- What are the chances of success, and how good would success be?

- The Ford Foundation more or less created the field of “public-interest Law” in the 70s and 80s. If it was possible then, it’s now. (Here to There: Lessons Learned from public-interest law).

- Because I am advocating for a general movement, not a concrete action, both success and failure are difficult to measure. Having a plethora of prestigious (technical) post-university hedges seems challenging in the short term. But, there is a clear movement for it with the public-interest tech university network (PIT-UN). I won’t dig into this question yet.

- What would have happened otherwise?

- The default is bad hedges. This means Mckinsey, this means Google, this means pure-math PhDs. (Note: working at Google, McKinsey, or doing a pure-math PhD can be a fantastic thing to do, but there are more direct and beneficial ways to have a positive impact).

- The default is that people who either do not really understand technology or do not critically consider doing-good, get over-optimistic with Tech-for-Good, and they emphasize Tech more than they emphasize Good. (One of my favorite articles of this is by Ben Green on The False Promise of Algorithmic Fairness: Epistemic Reform and the Limits of Fairness).

Criticism of my idealism.

It’s important to be skeptical of anything done in the public-interest. The very definition that I gave, means that it isn’t naturally addressed by a capitalist market, and so it needs to be more-or-less manufactured. Metrics of success in public-interest are difficult as poorer people have less money (by definition). But just because public-interest technology isn’t addressed due to market failure, doesn’t mean this shouldn’t (or more importantly: can’t) be addressed.

Some important considerations are : we are in an absolutely critical time period and likely the most important century of all time (future and past) - now is the time for bigger and newer ideas. Governments have in fact produced incredibly positive changes, even without market pressures; don’t forget that the US government is the most powerful entity in the history of the world (which is ironic, because so many people seem to equate the US government with the DMV). And communities like open-source software and hardware are in fact able to make radical changes to society (Redhat was able to become a 34 Billion dollar company, based on free, open-source software).

However, the most encouraging thing to consider is that better hedges in public-interest tech are possible because we’ve done it before: in the development of public-interest law. Starting in the late 1960s, organizations like the Ford Foundation started making strategic investments in public-interest law; and over the course of ~50 years, public-interest law went from a nascent idea into a serious career path, growing the the number of public-interest law centers from 92 to over 1,000 in early 2000.

I strongly recommend looking into this report by Freedman Consulting article “Here to There: Lessons Learned from public-interest Law”, which studies analogies between the past development of public-interest law, and the future development of public-interest tech.

Actionable items:

Okie, we’ve pontificated a whole bunch, but what would this actually look like? What does it mean to promote better hedges in public-interest tech?

First off, it’s important to ask: Are “Better Hedges” already happening?

Yes, programs like this already exist; like Venture for America, Aspen Institute’s Tech Policy Hub, US organizations like U.S. Digital Services, or fellowships like the Congressional Innovation Scholars Program, Presidential Management Fellows (PMF), The AAAS S&T Policy Fellowship, or Civic Digital Fellowship. And nearly anything from Resources for Working in Public-Interest Technology falls squarely in this category.

As an individual you can:

- Participate in organizations like the ones listed above.

- Give money to similar organizations.

As an individual in a community (in particular, the EA community), we can:

- We can “deploy” prestige by talking about such organizations more and changing our view on what is useful career capital to be more aligned with public-interest.

- We can emphasize the creation of early career capital organizations and fellowships, through grant-giving.

Donors, Philanthropists, Think Tanks, and Government organizations can:

(Much of this is taken from Here to There: Lessons Learned from public-interest Law)

- Work on the development of more fellowships and TFA-like organizations.

- Study planning of Public-Interest Law development: Philanthropy should consider continuing substantive research and strategic planning into the development of public-interest programs, similar to how public-interest law developed. Further research into these analogous situations is recommended.

- Develop diverse funding mechanisms: public-interest tech should seek to draw its funding from multiple sources (foundations, government, and private industry). People who are experts (or even just interested) in fundraising should consider developing robust funding mechanisms for public-interest tech fellowships.

- Target education: organizations we should focus our energies on developing ways for people to get involved with public-interest technology during their studies.

- Leverage Corporate Allies: The American Bar Association (ABA) is aware of the power of prominent allies. ABA remarked in the “it is large law firms which have the expertise and resources” to conduct “major impact” public-interest work, and by involving big-firms ABA not only gets better training for young lawyers, but also gained financial support from firms for the public-interest law program. We should look to building pro bono-like pathways for technologists to be involved with projects on a limited or part-time basis, and using the financial resources and visibility of major technology firms to build the field.

- Look Internationally: One crucial outcome from the growth of the public-interest law field in the United States has been the international spread of the field. International knowledge-sharing could be useful for developing the public-interest technology field, particularly given that the Internet and technology generally connect people across the world, and that other countries are asking similar critical questions.